Three or more generations living under one roof is more popular than ever, and it didn’t take long for the Cohen-Roach family to find out why.

Sal Cohen was living solo in a 3-bedroom house in Seattle when his daughter’s plans to build a home in a nearby city fell through. In short order, Cohen found himself with five new roommates: his daughter and son-in-law, their two energetic young sons and a friendly pit bull that lives for table scraps.

For Cohen, the change was seismic. After long enjoying the run of his house, his domain shrank to just his bedroom and bath. His grandson’s toys began popping up everywhere. Meals became more lively. Suddenly, he was among the 18% of the U.S. households living in a multigenerational home.

Multigenerational living, where three or more generations reside under one roof, has taken off in recent years. One study, conducted by the non-profit Pew Research Center, found that 60 million people lived in multigenerational households in 2021, four times the number that did in 1971. The number one reason people in the Pew survey cited as their “why” for multigenerational living was financial; doing so helped save money on housing costs, child care and food.

While there are benefits of a more affordable living arrangement and an opportunity to deepen family connections, living with extended family is a decision home buyers shouldn’t take lightly.

“I don’t think it’s for everybody,’’ Cohen says. “You really have to have the right combination of people.” Considerations around space and privacy and cohabitation-friendly layouts also can make the difference between a harmonious household and one where everyone’s nerves are frayed.

Cohen knows more than most people about how a home’s layout affects the experience of daily living: for nearly 40 years, he’s run his own home-building company, Homes by Sal Cohen, specializing in larger homes. Now, he’s seen up close how a few floor plan tweaks — plus rules to live by — can improve the experience for multiple generations living under one roof.

We asked Cohen and Hao Dang, a Zillow Premier Agent® Partner who also has first-hand experience, to share what they learned from their experiences with multigenerational living and offer some tips on the kinds of spaces that tend to work best for multiple generations sharing the same roof.

The value of space

Hao, who runs the Hao Dang Team in Bellevue, Washington, has sold scores of homes to clients who live with their children and parents or in-laws.

“Space is the most important thing,’’ Hao says. ”With people working from home and the need for home offices, everyone wants at least four bedrooms, minimum. Most times, when you’re looking at multigeneration, it’s usually a house over 4,000 square feet.”

Upsizing may seem counterintuitive in the current housing market. But the math works when you consider the cost of two households, says Hao.

He reasons: A larger home with more bedrooms — or a separate 1,500 square foot Accessory Dwelling Unit for parents or adult children — would cost upward of $2 million in Hao’s market, he says.

It’s an eye-popping sum, but it’s still less expensive than buying two homes in the Bellevue area, where even a 1,500 square foot rambler costs at least $1.3 million, he says. Given those numbers, housing two families in two homes would cost at least $2.6 million.

When you add in savings on utilities, food, transportation and potentially thousands a month on child or adult caregiving costs, multigenerational living makes a lot of sense, he says. In the Pew survey, 25% cited adult caregiving and 12% cited child care as the chief drivers behind their decision to join households.

The math may be different for every metro, Hao says, but the concept is the same: buying and maintaining one home is cheaper than two.

Adding space for family could also mean future rental potential if circumstances change and the space is no longer needed. Zillow® research shows that home buyers are increasingly looking to rent out all or part of their homes, so Hao says a lot of buyers love having that flexible space.

“You can certainly live all together, or live in a completely separate space,’’ he says. “If you want, you can have a friend or family live there or rent it out so that person is paying a portion of your mortgage. A lot of people really love that.”

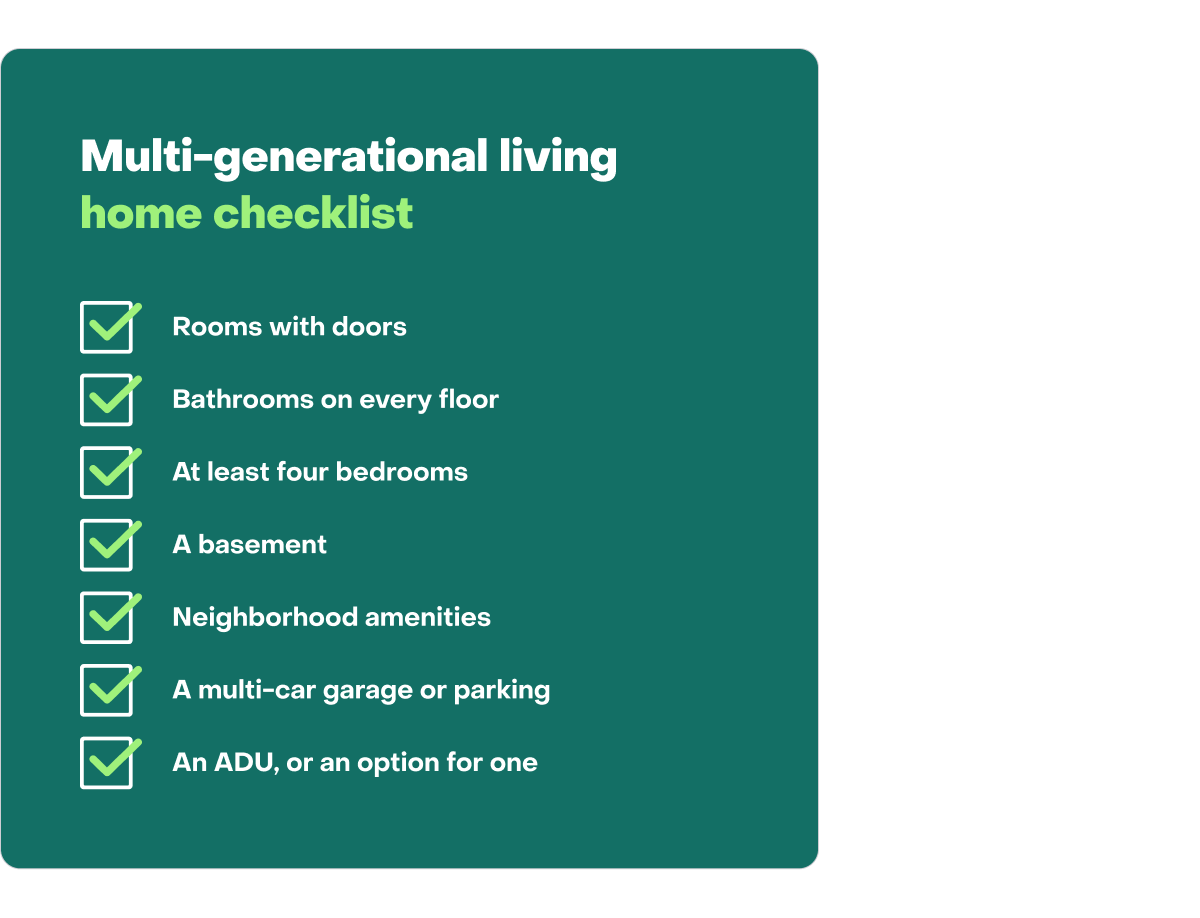

Multigenerational living home checklist

Hao says he directs clients shopping for a multigenerational home to look for homes with basements, dens or bonus rooms where families can gather or go for quiet time, away from the activity in the rest of the home.

His other top recommendations:

Rooms with doors

Open concept layouts are great for gathering, but Hao says everyone should be able to find a space where they can close a door and be alone. That’s especially true for people who work from home, and need privacy for Zoom calls.

“They don’t necessarily need to have windows,” Hao says, “but they should have doors so you can block out the sound. If you have multiple doors you can block off, you won’t hear a person at all.”

Multiple levels

A bedroom and bath on the main level is ideal for grandparents, Hao says. “Ideally, there should be a bathroom on every level of the house,’’ he says.

At least four bedrooms

This depends on the size of the family and whether people are working from home, but if there are children, parents and grandparents, having four bedrooms gives everyone some breathing room. Hao says three bedrooms isn’t usually enough space when you have a house full of people.

A basement

Basements can be the ultimate getaway. A door at the top of the stairs and a door to a bedroom, office or playroom makes for a quiet escape, says Hao. Without a place to hide out for a while, the only other alternative is to leave the house.

Neighborhood amenities

Some multigenerational homes are in established communities and some are in newer developments where there aren’t many amenities, says Hao. “The parents want to be in an area where it’s walkable, either to stores, coffee shops or grocery stores, or walkable where there’s sidewalks to parks and so forth.”

If the grandparents are going to be home with the kids, they need to be able to get some fresh air and exercise. “Besides saving money, that’s one of the more important factors,’’ he says, noting that flat terrain tends to be better than lots of hills.

Parking

In urban areas without good transportation, having space for multiple cars is important, especially as kids get older or caregivers come into the picture. Grandparents who are driving also need a place to park.

An ADU, or an option for one

Sal Cohen says he considers ADUs — separate dwellings either attached to the home or somewhere on the property — to be the perfect setup for multiple families. “An ADU can be designed so that it opens to the rest of the home and provides easy access to each other while simultaneously providing privacy,’’ he says. Ideally, the unit would have a bedroom, bath, small kitchenette and a living room/dining area.

Detached ADUs can eliminate the need for an oversized home, and provide a way to build flexibility into a home, offering the potential for future rental income or living space for adult children who might return home to live with their parents.

Weighing the rewards

Sal Cohen’s older daughter, Dominique Cohen, says her dad’s 3 bedroom, 2.5-bath home has great communal spaces, with its upstairs office/playroom and open concept living room/kitchen that makes it easy to keep eyes on the kids while whipping up dinner. But it lacks the kind of private space that allows someone to step out of the flow, especially in a busy household with active kids.

In fact, Dominique’s husband, Geoff Roach, says he initially worried about encroaching on his father-in-law’s space, and about how their relationship would evolve. “Who hasn’t had a roommate that hasn’t worked out?’’ he says.

Those fears, however, proved unfounded. “I feel very grateful,’’ says Geoff. “I lost my parents when I was very young, so it’s nice to have a father figure in the house. Other people might take that for granted. I don’t. I absolutely respect him. He’s a role model.”

That gets to another point about multigenerational living: while it can have its disadvantages, it can be enriching in many other ways besides financial.

The Pew survey found that 57% of adults in multi-generational households reported their experiences as very or somewhat positive, while 14% said it was somewhat negative. Only 3% said it was very negative. A majority (54%) also said that living with adult relatives other than their spouse or partner was rewarding all or most of the time, with little or no stress (36%). Still, 40% described the living situation as stressful some of the time, and nearly a quarter (23%) said it was stressful all or most of the time.

Stress can come from numerous factors, but Hao cites interference as being one area to consider. Having others stand witness to your choices and weigh in on them can lead to hard feelings and resentments if they’re not discussed — or discussed too much. “If you can live with your parents, I think it’s awesome,’’ says Hao. “ But, you know, they have a lot of opinions.” For instance, they may weigh in on how you’re raising your kids or the amount of hours you’re working or your dietary habits. Unless you can let things roll off your back, home life could get tense.

For Sal Cohen, the upsides of multigenerational living far outweighed any downsides. Having worked long hours when his two daughters were young, he loved seeing his grandsons grow and learn new things.

“It was great for me to be able to bond with the grandkids,’’ he says. “They got to know me very well and I got to know them. It’s really fun to watch them grow up.” He also enjoyed most mornings when the kids excitedly ran into his room to wake him. And then there were the shared TV shows, nightly family dinners where the adults took turns cooking and golf outings with his son-in-law.

Of course, anything involving people is going to have complications, especially if there’s dysfunctional family dynamics, or if people don’t share the same values or their lifestyles are incompatible. But with healthy dynamics and flexibility, multigenerational living can help reduce life’s stresses.

The key to harmonious living

“Communication is number one,’’ says Geoff Roach. Keeping track of schedules with three kids and making sure everyone is on the same page minimizes conflict and the chaos of running a household with small children — ages 7, 2.5 and 4 months — and two working parents, both of whom run their own companies.

Hao says clear communication helps avoid hurt feelings and resentments that can build if people’s expectations are misaligned. For example, his in-laws cooked dinner every day, so he would make sure to give them a head’s up early in the afternoon if he would be eating out so they wouldn’t feel slighted. It also helped that they shared similar philosophies about raising children.

“Just having the same morals and the same upbringing, I would say, makes a world of a difference,’’’ says Hao.

Although some families live together permanently, that’s not always the case. The Pew survey found that 41% of adults in multigenerational households say their living arrangement is long-term, while 34% say it’s temporary. About a fourth (24%) say they don’t know what to expect.

The Cohens fell into the later category.

When Dominique had her third child a year and a half into the living arrangement, Cohen opted to live on his own again in a home nearby. With space already at a premium, Cohen realized he would have even less of it with a new baby on the way. He also felt the need for private space that extended beyond his bedroom door.

“It’s very noisy with two little beings,’’ he says. “It’s more chaotic and there’s more stuff in the house.” A different floor plan that included a separate living space and a small kitchen would have been ideal, he says.

Now, Cohen stays connected to his family through work, baby sitting and weekly family dinners, joined by Sal’s youngest daughter, Gabrielle, and her rescue pup, Cookie. As the family joined up for a home-cooked meal on a recent Wednesday night, the kitchen filled up with the sounds of chopping, sizzling, a 2.5-year-old’s repeated questions and laughter.

Says Dominique, “The number one thing that made it all work, is we’re all easy-going. None of us is stuck in our ways.”

Photos by Adair Freeman Rutledge